This week we are featuring an essay written by Lei Marshall. Read more about Lei, and her essay titled “Lōkahi – Balance” below.

Aloha,

Aloha,

My name is Leionaona (Lei) Marshall and I am from Wai‘anae, Hawai‘i. I graduated from Central Washington University with my Bachelors of Science in Biology and am currently in the Accelerated Nursing Program and will graduate this summer. I plan to work as a pediatric nurse and eventually return home to Hawai‘i to serve my own community.

For most of my life, I struggled with my Native Hawaiian identity and establishing a meaningful connection with my culture. Unaware of the profound impact of colonialism and historical trauma, I failed to comprehend how these forces affected my understanding of my own identity, and the impact it had on the identities and connections of countless other indigenous communities. As I continue my journey of rediscovery, learning, and reclaiming my own sense of self, I hope to empower and amplify the voices of other indigenous individuals and

communities. Regardless of where you are in your journey, I encourage you to embrace your own unique story, honor your history, and take pride in who you are, and the legacy passed down to you from your ancestors.

I am a proud mother, wife, daughter, sister, and Kanaka Maoli. Mahalo nui loa.

Lōkahi – Balance

By: Lei Marshall

Mauli Ola– health. What is it? Every person has a unique interpretation of health shaped by their personal experiences and, even more significantly, influenced by their cultural background. Yet cultural integration in healthcare is not often seen in Western medicine, which tends to adhere to standardized practices and protocols. According to the National Cancer Institute, Western medicine is defined as “a system in which medical doctors and other healthcare professionals treat symptoms and diseases using drugs, radiation, or surgery.” However, even though the United States spends the most money on healthcare globally, it also has the highest prevalence of adults with multiple chronic conditions, obesity, and one of the highest rates of suicide. There is a huge disconnect between health and culture in Western medicine, a disconnect that could potentially solve many problems we see today.

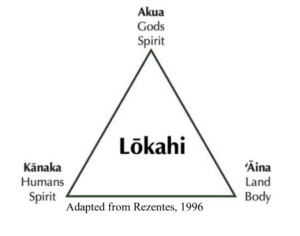

Before Western contact, indigenous communities had rich cultures and developed traditional practices and medicines. Tragically, a significant number of these traditions were suppressed or even banned as a result of colonization, depriving these communities of their ancestral knowledge and healing practices. Prior to Western contact, Native Hawaiian forms of healing/medicine included: lā‘au lapa‘au (herbal medicine), lomi lomi (massage), and ho‘oponopono (conflict resolution). These practices addressed the physical, psychological, and physiological aspects of health. In Native Hawaiian culture, health is a collective concept that extends beyond an individual level to family, community, the natural world, and the spiritual realm. They achieve health by following the Lōkahi (harmony/balance) triangle, which involves harmony between kānaka (humankind), ʻāina (land), and ke akua (god or gods). Illness or disease results when there is an imbalance, and restoring balance restores one’s health.

Cultural integration into health services requires incorporating both traditional and contemporary knowledge. Western medicine often prioritizes pharmacological or surgical interventions without considering incorporating cultural practices as an option before resulting to invasive treatments. Integrating cultural elements into a patient’s health management not only expands their range of treatment options but also empowers them with autonomy in selecting their preferred approach to treatment. This fosters a strong rapport and trust between healthcare providers and patients, enhancing the overall quality of care. A clinic located in O‘ahu conducted a study where they provided both Western medicine and Kānaka ‘Ōiwi (Native Hawaiian) healing practices, particularly lomi lomi. The findings revealed that 76% of patients believed that optimal healthcare could be achieved by combining Indigenous and Western treatments (Oneha

et al., 2023). Including culturally relevant interventions and integrating them into patients’ care is crucial as it addresses current symptoms and diseases and enhances patients’ health outcomes by fostering collaboration, respect, and a deeper connection to their health and culture. Minorities often face the label of noncompliance, but when we delve into the underlying reasons why patients may struggle to adhere to their treatment regimen, it frequently stems from a lack of cultural understanding and respect.

The consequences of colonization continue to affect indigenous communities leading to ongoing suffering from historical trauma. This has resulted in the loss of significant cultural traditions and practices, leaving families and communities grappling with the challenge of reclaiming their identity. In the face of these circumstances, incorporating culturally sensitive care into health services represents a modest yet meaningful step that the United States and Western medicine can take to facilitate the healing of trauma, foster the restoration of trust, and assist communities in reconnecting with their authentic selves. Integrating culture into Western medicine is more than just another means of treatment, it is staying connected through generations, optimizing health for not only yourself but your community and environment.

It is clear that the U.S. is a broken system—a system that prevents equitable access to culturally sensitive care. Not only does the system fail to integrate cultural practices into Western medicine, but also fails to include indigenous communities in decision-making processes. Culture is appropriated, not appreciated. It is time we remember the intrinsic value of cultural diversity and the profound impact it has on individual and community well-being. In doing so, we can begin to rectify the injustices of the past and shape a more compassionate future. By actively listening to indigenous voices, respecting their knowledge systems, and co-creating healthcare solutions, we can honor their resilience and wisdom.

References

Oneha, M. F., Spencer, M., Bright, L., Elkin, L., Wong, D., & Sakurai, M. (2023). Ho’oilina

Pono A’e: Integrating Native Hawaiian Healing to Create a Just Legacy for the Next

Generation. Hawai’i journal of health & social welfare, 82(3), 72–77.

Oshiro, K. H. Office of Hawaiian Affairs, Research Division, Demography. (2015). Native

Hawaiian Health Fact Sheet 2015. Volume III: Social Determinants of Health. Honolulu, HI.